|

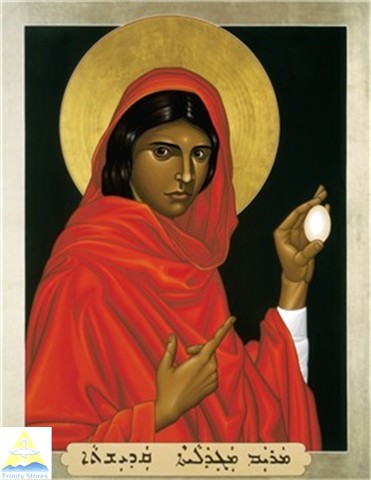

| Icona de Santa Maria Magdalena a Grace Cathedral, la seu anglicana de la Diòcesi de Califòrnia, a San Francisco. |

Why are so many women named "Mary" in the Gospels? The Aramaic name Maryam (Miriam in Hebrew) was popular among Jews in Palestine during the first century; being named after Moses' sister was auspicious. Maryam in Aramaic became Maria in the Greek Gospels, a short step to Mary in English.

To distinguish one person with a common name from another, place names could be used. That is why Jesus (from the Aramaic equivalent of Joshua) was called "of Nazareth." So we have, in addition to Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary of Bethany and Mary of Magdala -- or Mary Magdalene.

Unattached to husband, father or brother, the Magdalene stood out within Jesus' fellowship in a culture where women were expected to live under male protection. When Jesus said that prostitutes had a better chance of entering God's Kingdom than his opponents did (Matthew 21:31), some people came to the conclusion that Mary Magdalene fit the category.

Medieval imagination took that possibility and exploited it. Mary Magdalene was conflated with a much later Mary (Mary of Egypt), and given an itinerary that took her to Jerusalem, through conversion, and then on a trip on a rudderless ship guided by an angel to the south of France. There, it was said, after winning souls to Christ and destroying idols, Mary Magdalene retreated to a mountain cave, where she levitated when she said her prayers, and ultimately died on July 22, her feast day.

Another legend has it that, unattached as she was, Mary became Jesus' concubine. That was a claim asserted by the Cathars, Christians who became the objects of an internal Crusade declared by Pope Innocent III. His zealous executioners destroyed the entire city of Beziers for the insult to Mary Magdalene, carrying out the genocide on her feast day in 1209. Yet the idea lost none of its appeal; later Martin Luther embraced the Cathar view of Jesus' liaison with Mary Magdalene.

Imagination did not end with the Middle Ages. Pierre Plantard, a right-wing and anti-Semitic pretender to power in France after the Second World War, tried to provide evidence - in the form of faked parchments he deposited in the Bibliothèque Nationale - that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had born a child. Plantard's claims ultimate gave us the appealing fiction of The Da Vinci Code.

History is also a form of imagination; its power lies in its insistence on evaluating evidence and its refusal to bend to a preconceived program of what the findings should be. History reveals a stronger Mary Magdalene than the predominantly male projections that have reigned from the time of Jesus' critics to her sexualized portraits in New Age fantasies.

Mary Magdalene is the only person in the Gospels named as being exorcized by Jesus, freed of seven demons (Luke 8:2). During this prolonged cure, Jesus initiated Mary into his particular understanding of exorcism. For Jesus, people taken on their own were as clean as God had made Adam and Eve. If a person became unclean or impure, that was not because of contact with exterior objects. To his mind, impurity was a disturbance in that person's own spirit that made them want to be impure, a disturbed desire to pollute and harm themselves.

Uncleanness had to be dealt with in the inward, spiritual personality of those afflicted. Mary Magdalene had reason to understand these principles better than most people, and it is not coincidence that the most detailed stories of exorcism in the Gospels come from places near Magdala, where she was active as a teacher both before and after Jesus' death.

Anointing, in addition to exorcism, was a signature ritual of Jesus. Mark's Gospel (6:13) reports that, when his disciples went out to offer Jesus' healing therapy in his name, "they threw out many demons and anointed with oil many who were ill, and healed them." Anointing conveyed Spirit to Jesus' mind, and he wanted his followers to anoint people.

When Mary anointed Jesus near the end of his life the other disciples were angry with her (Mark 14:4-5). But Jesus explained the significance of what Mary Magdalene had done. Anointing the dead was a traditional part of Judaism, and he saw that Mary - by anointing him - connected the spiritual healing of his days in Galilee with the possibility of his execution in Jerusalem. Just as human life could be transformed by the inflowing of Spirit, so death itself could become the vehicle of God's presence. Jesus insisted, "Wherever the gospel is preached in the whole world, what she has will be spoken of in memory of her" (Mark 14:9). The full insight that suffering can become a medium of divine presence came to Jesus through Mary's anointing, and he ordered it as part of his message.

Mary's dedication to the ritual of anointing extended beyond Jesus' death. To complete the dutiful care of their dead rabbi, Mary and other women made their way to the tomb. Perfumed oil for rubbing on the dead was scented with the resin of myrrh and the leaves of aloe (John 19:38-39). Mary's vision at the tomb of Jesus marks his separation from his flesh and his entry into a resurrected existence. "He is raised, he is not here," an angel says (Mark 16:6). Jesus himself described those raised from the dead as "like angels" (Mark 12:18-27; Matthew 22:23-33; Luke 20:27-38). Mary Magdalene's vision, precisely because it was a vision in the earliest account (Mark 16) and not the inspection of an empty tomb, placed Jesus in the realm of heaven.

Beneath the complicated legends of medieval hagiographers and the conspiracy theories of their modern revisionist counterparts, Mary Magdalene's signature sacraments of exorcism, anointing, and vision persist. Her three gifts of Spirit are her inheritance: dissolving what is impure or evil, offering ointment for sickness and discernment, and vision to perceive the spiritual truth of resurrection.

Whether Jesus and Mary, two unattached people, ever entered into a sexual relationship is not a historically answerable question. But their intimate connection in the world of ritual is as plain as the continuing power of the practices they pioneered.

Bruce Chilton is the Bernard Iddings Bell Professor of Religion at Bard College and author of Mary Magdalene. A biography (Doubleday).

Font: huffingtonpost

Cap comentari:

Publica un comentari a l'entrada